陳原君 | Yuanjun Chen | What We See When We’re Biking in Omaha

I. The Protest on Harney Street

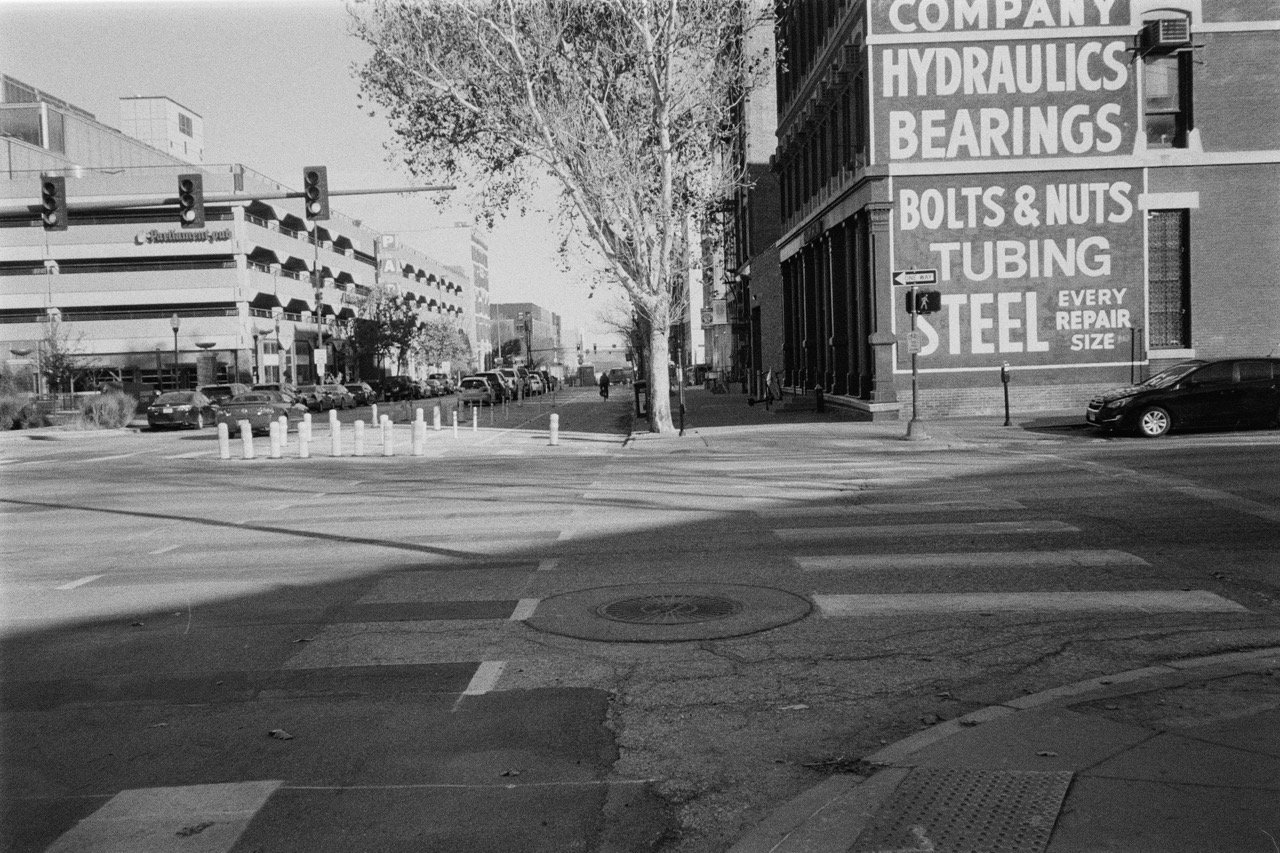

On the evening of September 29, 2022, a protest took place at Dewey Park to oppose the removal of the Harney Street bike lane. Stretching a mile and a half, this was Omaha’s first protected bike lane, connecting Midtown to the Old Market. Traffic poles and street parking acted as buffers, keeping cars safely away from cyclists.

Since its debut in the summer of 2021, this short-lived but innovative lane quickly gained popularity among local commuters for its added safety features. Less than two years later, the city announced plans for its removal, citing excessive maintenance costs. The news quickly spread through the biking community, upsetting many who had come to rely on the lane. To join the protest, I skipped an art history class and drove to Dewey Park, with my green Bianchi strapped to the bike rack and a box of cameras.

I wanted to create a project highlighting the challenges cyclists in Omaha face. The city’s traffic design heavily favors motorized vehicles, with little infrastructure to make the hilly streets safer for cyclists—some of whom may not have access to cars, even during the cold winter months. Despite these obstacles, I enjoy the insights and unique perspectives that come with biking. I believe cyclists notice things that drivers cannot. To capture these perspectives, I sourced a dozen old analog point-and-shoot cameras and planned to invite local riders to join me in a photo project.

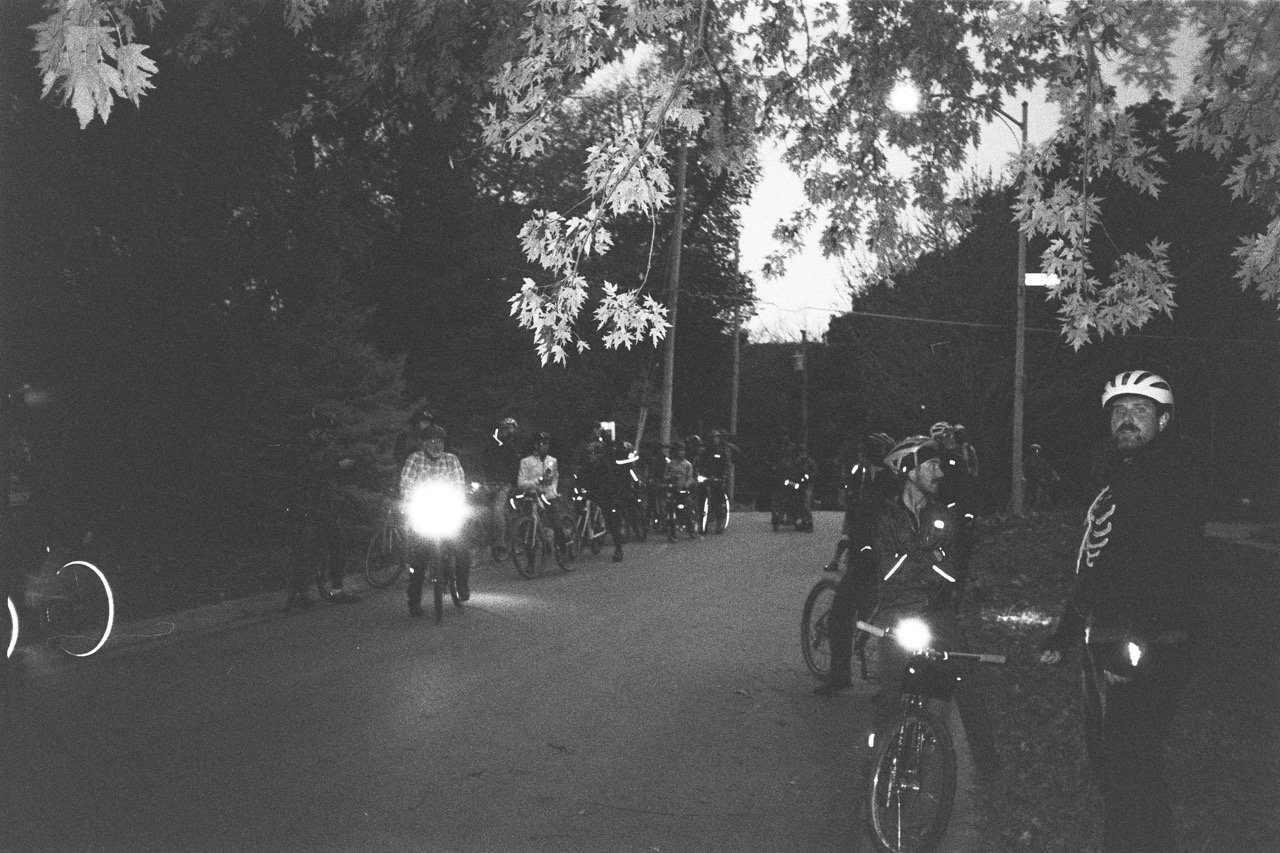

By the time I arrived, a large group of protesters had already gathered in the park with bikes. People were chatting, sharing their frustrations with the city’s plan. News reporters were also present, filming and interviewing the crowd. After a while, the protesters mounted their bikes and began riding in a loop along Harney Street, 24th Avenue, St. Mary’s Avenue, and Turner Boulevard. A video of protesters riding up the Harney Street bike lane is still available on the websites of local news outlets, KETV Omaha and The Reader Omaha.

I shared my idea with other bikers, giving away twelve cameras, all loaded with Ilford HP5+, a popular British black-and-white film. The instructions were as follows:

“Only use this camera when you are biking outside. Photograph areas you find underrepresented or dangerous for cyclists. Or simply capture moments when you are having fun riding your bike.”

Hours after the protest, the plan for removal was postponed. Thanks to financial support from a local donor, the bike lane remained in place for another two years, ultimately closing in the fall of 2024 to accommodate streetcar construction.

By the summer of 2024, seven cameras were retrieved. I developed all the negatives and selected the most relevant images for the following pages. The chosen photos came from four participants, as the other three rolls were either blank or unusable.

Photos by participants follow:

A special thanks to JH, BD, SS, WR, DW, DL, and KS for returning cameras #3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 11.

II. Do You know?

In my free time, I enjoy biking and photography. For some reason, well-made steel bikes and fully mechanical cameras attract me—much like bad eggs attract flies. Quality gears paired with performance, durability, and maintainability make these the perfect tools for me to interact with the world. While a bike allows me to travel farther, a fully mechanical camera enables creativity even in the coldest winter. With proper care, they can outlast my human flesh and serve future generations, unlike my soon-to-be-outdated smartphone. Though biking can be challenging for some, it is a contraption powered by nothing but human effort and requires no gas or electricity. A healthy rider with food and water can cover over 100 miles on flat terrain in one day. Honestly, a bike is so practical it might as well be on a post-apocalyptic survival list—right next to fishing rods and a compass.

Riding a bike lets me observe my surroundings in greater detail, takes me to places that I wouldn’t see if I were driving, and allows me to measure the landscape with my body. It keeps me in shape and teaches me which hill I can climb in one breath. I could stop behind an old church and look at its bricks and pattern. The slower pace of biking allows me to notice how people from different neighborhoods spend their free time with their families, how houses are decorated, and the correlation between the landscape and urban planning.

It’s fair to say cycling creates a deep connection between my body and my passion for geography and anthropology. Most importantly, it allows me to stop and take a picture without worrying about blocking traffic.

Over ten years ago, my father gave me a film camera, which sparked my passion for film photography. The inability to playback, as well as the cost of each exposure, taught me to be more intentional with every shot. Furthermore, I also adore the rendering of film, whether in color or monochrome. After moving to Omaha, this practice was significantly impacted when the cost of film processing tripled. I couldn’t afford to photograph like before, and I also couldn’t get to the photo lab without using Uber or Lyft. It was hard to continue my practice, even though I preferred the slower process. I kept shooting and passively allowed the pile of undeveloped film to grow, some of which I waited two years to develop. To access my photographs quickly, I have slowly adopted photographing digitally.

In 2020, during the pandemic, I bought my first bike as an adult and got my driver’s license and a car for the first time at the age of 24. This was quite late compared to my American peers, many of whom obtained a driver’s license before they turned 18. Having both a bike and a car was life-changing—like unlocking the greater map in a video game. Grocery shopping no longer meant carrying a gallon of milk and a dozen eggs uphill in the cold, and the outdoors was no longer limited to Elmwood Park. During the summer, I would explore the city by bike with a camera on my shoulder, wandering between different neighborhoods and my apartment. It didn’t take long for me to realize that there were hidden truths to biking in Omaha.

III. Biking in Omaha

As a former international student, I understand that my need for bike lanes may not fully align with the needs of the larger community of bike commuters. I lived in an apartment complex close to UNO’s Baxter Arena before graduation. I would ride across Elmwood Park and the campuses for school, and to the nearby grocery store when food ran out. Next to the complex, there was the Keystone Trail, a paved pathway alongside Little Papillion Creek used mainly by bikers, walkers, and joggers. The creek brought life to the area—geese gathered and left droppings on the trail, birds nested under the bridge and flew back and forth like in a beehive, and my favorite: riding through seas of fireflies on dark summer nights. Countless green dots glided out of sight, the magical view almost resembling an ancient analog computer animation. Sometimes, I would hop on the trail with my bike and try to get as far as possible.

Omaha has several longer, continuous trails like the Keystone Trail that follow the natural landscape. These are arguably the city’s most enjoyable bike infrastructure, often situated alongside creeks or around a lake.

Because they are closed to motorized vehicles, these trails are ideal for cyclists seeking to ride at higher speeds. Interestingly, many cars with empty bike racks can be seen in the parking lots along these trails, as people often have to drive to the trailhead before starting their rides.

Despite these enjoyable trails, bike infrastructure is severely lacking for traveling in the city. As I started exploring Benson, Blackstone, Old Market, and North and South Omaha, I often had to use the sidewalks to maintain a distance from cars. Sometimes, I even had to ride on the road to avoid broken glass or damaged sidewalks. One of the worst areas was South Saddle Creek Road. Although it has a relatively flat elevation, making it more suitable for bike traffic, the lack of bike lanes, high vehicle speeds, and poor sidewalk conditions made it both challenging and hazardous. Sometimes there are painted lines on the ground marking the existence of a bike lane, like the ones on Saint Marys Avenue and Leavenworth Street, but the speed of vehicles and lack of physical barriers make it hard to feel safe while pedaling.

Many vehicles travel east-west on Dodge and Leavenworth Streets. The demand for bike infrastructure in these areas is obvious, but they remain some of the least enjoyable areas to ride a bike. There’s a lot of uphill climbing, and difficult to avoid interacting with traffic. Better bike lanes running east-west—like the one on Harney Street—are essential to creating an effective network of bike routes. After the Harney Street bike lane was closed for construction, it became hard to imagine seeing any improvement in the situation until the new permanent bike lane is completed in 2028. For the future of Omaha, I hope to see more extended bikeways stretching west beyond Saddle Creek, connecting the city to the scenic trails along the creek, and creating a safer environment for cyclists.

Currently, it is dangerous and inconvenient for pedestrians and cyclists to cross I-80 from 72nd Street. The sidewalk along 72nd Street comes to an abrupt end as the road merges onto the interstate, forcing pedestrians and cyclists to use the ramp and emergency lane without proper traffic signs or protection.

I’m not sure how the city expects non-drivers to navigate crossing the interstate, but I was both surprised and horrified by the lack of infrastructure when riding along that stretch, especially as vehicles cut me off to merge onto the highway. Despite both 72nd Street and I-80 being heavily trafficked by personal cars and semi-trucks, the popular intersection still lacks infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists.

According to Jacob from the Community Bike Project Omaha, cyclists report being hit by cars on a weekly basis during certain months. At the intersection outside of my home, it’s startlingly common to see drivers holding phones in their hands. “Out of sight, out of mind.” I worry that as fewer people ride bicycles nowadays due to the lack of infrastructure, drivers become even less aware of cyclists and more likely to drive without considering the safety of others.

IV. The CBPO

With nowhere to go during the pandemic, I attempted to restore my 1986 Bianchi as well as I could. Perhaps it was my way of coping with the pandemic and using up my extra energy. I unscrewed everything I could, took every piece apart, cleaned, polished, and re-greased. I also replaced the hardened brake pads and removed every bit of hardened grease and dust. During the assembly, I realized that I didn’t know how to adjust the derailleurs to make the bike shift properly, so I started searching for an affordable bike mechanic who could show me the process.

I came across a local nonprofit organization called the Community Bike Project Omaha (CBPO), located in a late 19th-century house near 33rd & California. Jacob from the bike shop encouraged me to bring my bike, provided tools and workspace, and guided me through adjusting the drivetrain. Thanks to CBPO’s technical support, my 1986 Bianchi Portofino now functions as if it just rolled out of the factory.

Through this experience, I gained a deeper understanding of the organization’s mission and grew more confident working on bikes. I quickly became a regular at the shop, often spending my free time there helping with small tasks.

CBPO is dedicated to helping individuals in need of affordable transportation by offering resources for bike repairs and maintenance. They rely on local donations and salvaged parts to support their mission. The shop features four workstations equipped with bike stands and tools, allowing anyone to work on their own bike. Additionally, they have a collection of old bikes waiting to be claimed and tuned up. Getting a bike from CBPO costs just a fraction of the usual price, and their in-store mechanic provides guidance on how to properly tune it.

V. More to Be Improved

In Omaha, traffic design prioritizes cars, often overlooking the needs of cyclists. Driving is the easiest option, but many people who face financial challenges don’t have reliable access to a car. Even if they don’t enjoy biking, it’s often their best way to get around.

The lack of bike lanes doesn’t just discourage people from going out—it creates significant barriers for those trying to escape poverty. Without safe bike infrastructure, commuting becomes a daily struggle, especially in winter when the cold and snow further limit access to job opportunities.

After years of advocacy, the city finally had its first separated bike lane on Harney Street. With a protest, it lasted a little over three years, then closed for construction. Without a separated bike lane for another four years, the risks and challenges for bikers will rise again. After hearing about cyclists getting into car accidents repeatedly, Omaha’s bike riders are tired of risking their lives.

Taking away the only protected bike lane was the final straw that broke the camel’s back.

It’s interesting to notice that some of the pictures from participants were taken in Council Bluffs, I like that their wide separated bike lane that conveniently parallel to the city’s main street, see page 187. Until we have more bike lanes in Omaha, please remind drivers to be extra patient with bikers on the road. We really appreciate it when drivers slow down and maintain a safe distance.

Last but not least, thank you to everyone who supported the making of this project.

December 8, 2024, Omaha

Yuanjun Chen

Yuanjun Chen (Jun) is a Cantonese interdisciplinary artist, born and raised in Guangzhou, China, in 1996 to artist parents Yi Chen and Yulan Zhou. In 2019, he moved to Omaha to study at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and graduated in 2023 with a concentration in printmaking.

Since high school, Jun has been passionate about photography. His photography can be found on Instagram under the handle @Suicide_Eggs. He also enjoys drawing on paper occasionally, and often uses his own photography as a reference.

Jun’s collaborative work often integrates writing and photography to explore themes of mobility justice, systemic inequities, and the experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities. His projects aim to offer fresh perspectives, encourage dialogue, and bridge cultural understanding.

Quarantine Calendar Project, 2020-2022—Jun’s last collaborative work. A visual archive of life during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comprising over 1,000 photographs from 19 participants across five countries, the project brings together diverse perspectives through a shared lens. Each participant contributed one image per day, capturing moments of isolation, resilience, and the intimate realities of a world in lockdown.