AC Interview | Sunshine Thomas-Bear + Annika Johnson

(From left to right) Annika Johnson and Sunshine Thomas-Bear

Recently, Associate Curator of Native American Art at the Joslyn Art Museum, Annika Johnson sat down with Sunshine Thomas-Bear, Director of the Angel DeCora Memorial Museum and Research Center and Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, to talk about the history of the Ho-Chunk People and tribal museums’ essential role in reinvigorating cultural lifeways. Listen to the full conversation below and read through the transcript for links to additional resources. If you’re on the go, visit Amplify’s Anchor page to stream the discussion on your favorite podcasting platform.

Transcription

Interviewer: Annika Johnson

Interviewee: Sunshine Thomas-Bear

Date of Interview: July 1st, 2021

List of Acronyms: STB = Sunshine Thomas-Bear; AJ = Annika Johnson

[AJ] Hello! Thanks so much for listening. My name is Annika Johnson. I'm the Associate Curator of Native American art at Joslyn Art Museum and today I have the pleasure of interviewing Sunshine Bear who's the Director of the Angel DeCora Memorial Museum and Research Center in Winnebago, Nebraska. We're going to have a wide-ranging conversation I'm really looking forward to this, Sunshine. Thanks so much to Amplify arts and to Peter for inviting us to have this discussion. So, let's kick it off. Welcome Sunshine. I'll let you introduce yourself.

[STB] First of all, thank you guys for asking me to do this. I really appreciate it.

My name is Sunshine Thomas-Bear. I am a member of the Bear Clan of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. I was adopted by Charles Bear, who is a member of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska and Eva Bear, whose maiden name is Bowman. She's a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee band of the Mohicans. My biological parents are Wilbur Wolf and Louise Thomas, and their parents’ names are Dave Cleveland, and Cynthia Wolf-Baker and Bernard Thomas and Erma Rose Kelsey.

I am a proud mother, and I would say my number one job is as a grandmother. I have one grandson. His name is Malcolm. My educational experience is I have an Associate of Science: Business degree from Little Priest Tribal College, a Bachelor’s in Education with an emphasis in ESL from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and I just finished another associate's degree in Native American studies at Little Priest Tribal College. I just graduated this past spring. I've also been looking into Native American Law. I'm hoping to get my foot in there, which is very relevant to my job, something that I need.

Before coming here to the position that I'm in now, I was a special education teacher at the Winnebago Public School, and it was absolutely my dream job. I left because I couldn't make ends meet. Living off the pay as a teacher, with all my kids and everything, I just couldn't do it. I couldn't make ends meet. I left the school and my students, which are my kids. I always think of them as my kids. I still watch them grow up. And then I went to the HoChunk Renaissance program, which I am also very passionate about. It is language revitalization within our tribe. I was the instruction coordinator and teaching our language within our schools. As you know, or may know, our language is at an emergency state with only five fluent speakers in our community. It's like a constant race against the clock with our language and culture because many of our language and knowledge holders are elders and one day, they're not going to be with us. We have to get as much information from them as we can before that time comes. We also fight the colonization of our own minds and some of our people struggle to see the importance of our culture and language and how that fits into their lives now that we're colonized.

Then, I started here at my current position. It’s a long title I'm the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO), the Cultural Preservation Director and the Angel DeCora Museum Director for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska as of March 2020. It's basically the same race from a different angle. I still work closely with HoChunk Renaissance and the school. I try to use my current position to continue my work towards preservation of our language and culture, finding and bringing our cultural items home to the museum, returning our ancestral and funerary objects whose journeys were disrupted when they were taken from their places of burial, and protecting the lands that we currently reside on, or have resided on, and our water in those areas as well. Along with this, I also work on cultural preservation, reintroducing cultural activities and arts to our people and learning and teaching what our elders know and sharing that with others. A lot of our classes focus on women, but I really work hard to find classes that our male relatives can benefit from as well and teach.

And as a woman, mother and a grandmother, anything I learned from my elders, or anyone, I then take home to my family and teach them. So, to me, that is how we are going to save our culture, our language, and our people, through our children. They're the most important piece in saving who we are, or who we were, trying to revitalize that. Without our language and culture, we're no longer a people. To me, without that, we're what the colonizers aimed for us to be, which is exterminated--we're no longer who we were. That’s what I do.

[AJ] You've been on a long journey, and you wear many hats. You're doing so much important work and I think it's important to move a little further back in time. I would love to hear more about the history of the Ho-Chunk people and how they came to be in Nebraska and that history of people coming from the Minnesota / Wisconsin area.

[STB] First off, I would like to say that I'm a student, as well. I am going to be a student for the rest of my life in our history and our culture and our language. There's so much to know and learn. I feel, at my age, even though I'm not super old, I feel like I'm way behind the time and like I should have started learning as soon as I was born to be able to learn even half of what I need to know to help my people. What I know is what I've been told and researched. I have an elder, Carolyn Fiscus, that I turn to for answers, and she helps me with a lot of the things that I'm doing.

As I begin this timeline, there's an important part of the issue that started before the removals. There was an introduction to the tribes who came into contact with settlers. For our tribe, it was fur trading with the French. This was our people's introduction to consumerism and, as we all know, we overbuy. We overbuy everything and that was our introduction. Our people, and other tribes before this, only took what was needed from the earth. And this was the start, to me, of our decline into colonization and, as we all know, from first contact came disease. Diseases our people had no immunity to killing 1000s, if not millions, of tribal nation peoples, exterminating whole tribes. And then, shortly after 1816, the fur trade made its own decline as well.

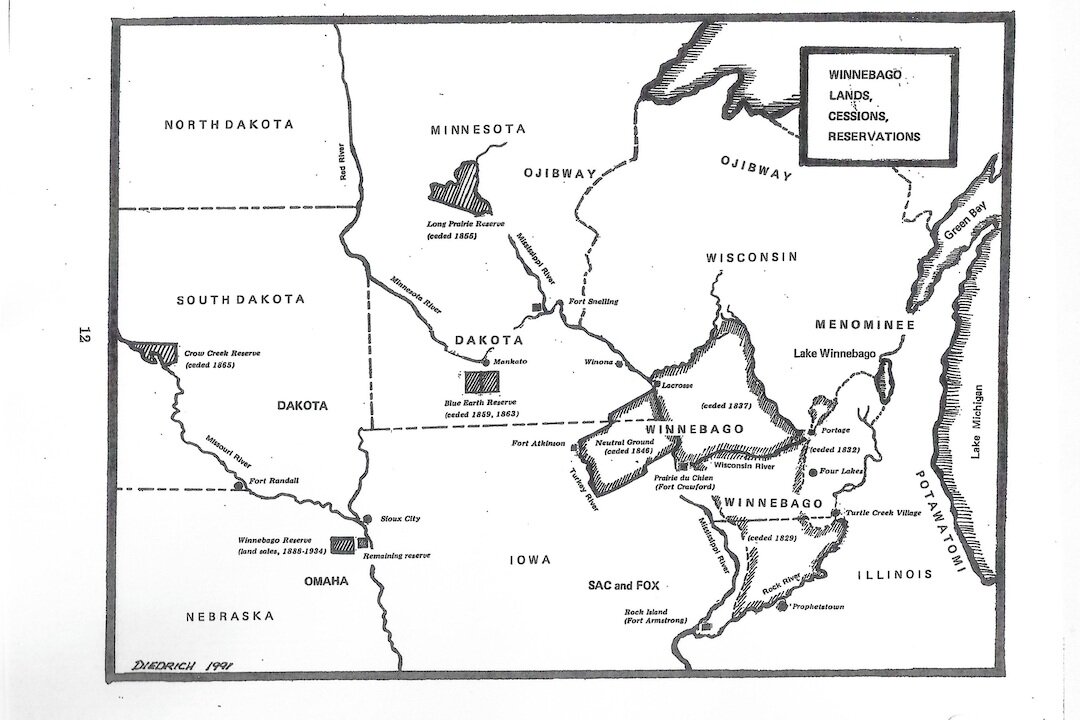

Our original homelands spread all the way to the Mississippi River from the Ohio River and west of Lake Superior. So that's basically, Wisconsin, Illinois, up toward Canada. Throughout all this, the new Americans, because this was a very new America, after the Revolutionary War, more land, more resources, whatever was found in our land was taken. We were moved again and again and not just our tribe, many tribes, all tribes. So, in 1816, the new US and settlers came along and began to take our land. They didn't move us out of our area completely, the area that I just mentioned, but they narrowed our homelands in Wisconsin and Illinois. The 1816 Treaty says Ho-Chunk would impose on settlers, so this began the breaking up of our nation. Settlers over-hunted our game and fishing. Also, during this time, lead miners came in because they found lead in Wisconsin and the Illinois area.

In 1825 was the establishment of tribal territories. 1829, in this treaty, all of Northern Illinois and two thirds of Wisconsin is taken in this treaty, which gave us even smaller territory. They were to stay away from Rock River and Sugar River for 30 years, which was the concession of the treaty. But, as we all know, the government did not uphold the things they agreed upon in treaties. Each new treaty that we signed stated that it made null and void the previous treaty, so that was always their wording.

For us, we're clans. We have 12 clans and there were a lot of us in the beginning. Each clan had their own area, so we were spread out through these lands. We weren't all together like we are now. If we go back to around this treaty time, the government grabbed what they called, “bread chiefs” and kept them hostage in Washington DC, this was around 1829, until they would sign treaties. Our “bread chiefs,” and I don't necessarily like that word, but that's what they were called, asked for two years to move from this land that was just made smaller land in 1829. They asked for two years to move after signing. They were unaware [the treaty] stated only six months. Of course, the leaders and their clan leaders told them not to sign anything, but they did because otherwise, they wouldn't be freed. They would have been killed if they didn't sign. So, when they got back home, basically people were upset at each other and this starts the decline in our clan system, and families as well, because we're fighting amongst each other. Shortly after they arrived home, troops arrived to ensure that they move. They thought that they had two years, right? They only had months to move.

In 1832, we lost more land in Illinois and Wisconsin south and east of the Fox River, and moved to neutral ground, or White Clans area, pushing all of us together in what is now Iowa and Minnesota. Like I said, it was unnatural for our people in clans to all be in this little area together. With this treaty, we were supposed to get a sawmill, a school, and other things, but of course, that didn't happen. During this time in 1832, Black Hawk, a Sauk leader, was retaliating against the government and things started to get heated and eventually come to a boiling point as we go through this timeline. The government began playing tribes against each other. Although there were rifts between tribes before first contact, nothing compared to how the government turned us all against each other, telling one tribe one thing, and another tribe something else, to get us fighting against each other, which is still very evident in our lives today and how our people treat each other. There's a term that I’ve heard over and over, which has turned into this lateral bullying and oppression that our people face and do to each other.

So, in 1837, again, all stipulations of previous treaties were null and void. We were pushed to the west side of the Mississippi into what soon would be the Iowa Territory. The treaty lessened the neutral ground area. We weren't there in that area very long--maybe six years at most. During this time, Black Hawk was raiding into Minnesota areas. In 1855, our tribe was moved to Long Prairie. That land wasn't good and we were near a tribe that you know we didn't necessarily get along with historically, so it was kind of tough for us there and a completely different environment than what we were used to. If you go up to Wisconsin and Illinois, it's hilly, trees, that type of thing. When you go into these other areas, it’s nothing like what we were used to. The game isn't what we were used to, because we lived off the land. We lived off of what was given. It's not like today where you can go to a store and buy what you need. We went out and hunted and picked.

In 1857, the tribe moved to Blue Earth. The government didn't bring the supplies and rations that they were supposed to bring, so they had to sell part of Blue Earth to survive, which is in Minnesota. In 1859, tribal leadership ceded land in Blue Earth, which basically sold the land there to help us survive for seeds, rations, food, because our people are dying. Our people are dying because the government isn't bringing the rations that it promised in these multiple, multiple treaties.

In 1863, as a lot of people are aware, due to the Dakota Uprising, which was in 1862, where 38 of our Dakota relatives were hanged, in 1863 they force marched our tribe to Fort Snelling. They were put on river boats, and on these boats, many of our people got sick from the various diseases, diseases that we had no immunity to, like malaria, and smallpox. Imagine putting a ton of people on one little boat. You're just going to continue to be sick. I'm guessing the boats were dirty and that there wasn't food on them. Once we were put on the boats, we were sent down the Mississippi and up the Missouri River to Crow Creek, South Dakota, and all of this was during the winter months.

I found something in my research that I wanted to read here. This was in the Daily Republican in Winona, Minnesota, their newspaper, in 1863. It states, “that the reward for dead Indians has been increased to $200 for every Redskin center purgatory. The sum is more than all the dead bodies of all the Indians east of the river are worth.” We were not only battling the government, but we were also battling settlers. They basically put bounties on us, at will, whenever they wanted to.

Back to our boat ride, the river boats. Some of our scouts jumped off the boat to talk to some of our Umóⁿhoⁿ relatives to try to find land and a place for our people. We knew that where we were being sent to our death. Crow Creek, South Dakota in the winter is horrible conditions. I don't know if you've ever been there. It's a very desolate land. You can't farm the ground. There aren’t many trees, and it was winter. Imagine that. We didn't have the resources we have today. There were no rations, there was no food. It was freezing cold, and many of our people didn't survive. Some stories I've heard of our people, they tried to make soup out of bark, boiling the bark. Mothers fed their babies corn from horse droppings, getting it out of the horse droppings and chewing it and feeding it to their babies for them to survive. There are multiple stories, and death when we begin this walk, what our people call “The Walk of Death,” and throughout these near 50 years. Then, to save our people, Chief Little Hill and Little Priest, we all escaped. We escaped to the land we reside today. Our Umóⁿhoⁿ relatives agreed to it so we could help protect them and act as a buffer between other tribes and them. We're a warrior society. That's what did. We were warriors and we have a very proud history, you know. But I think, in the end, this history is something to be proud of too because here we still are.

What I've heard of our escape is that we used dugout canoes and followed the creek until the Missouri River. And then we followed it down to, like I said, where we are now. I was told that when they got here, there were no babies, and no old people left. Only a few hundred of us that survived. Those people who passed away that we could bring with us, we pulled along behind our canoes, and this was in wintertime. Imagine a large tribe of 40,000 plus people being reduced to a few hundred in less than 50 years and the trauma, the historical trauma, and everything that goes with that. Then, in 1865, that treaty allowed us to stay where we are now in Nebraska. The government gave us money to buy half of the Omaha Reservation, and that's where we are today. With all of this, there's so much going on for our people, like I talked about, the depth of trauma, and also resilience. We didn't stop. We kept going. We kept trying to survive. There were tribal members who would run back to Wisconsin and hide out in our homelands, which is now why you see two tribes. There's the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, and also the Ho-Chunk Nation. So, we are two tribes, but we were actually one. That has also caused a divide between our people.

But that's just a real short, quick history of our people. As time goes on, there's the boarding school era, the Indian Removal Act, which took people from the reservations and just stuck them in various cities. My dad was a part of the boarding school era and also the Relocation Act, where he was in the boarding school. I know a lot of people are talking about boarding schools right now, but he was a part of the St. Augustine's [Indian Mission] Boarding School where he was sexually abused and abused. A lot of the boys there were. After that, he was removed to Los Angeles--just took a bus there and got off and had no idea where he was. He was given a little bit of money and told, “Here, this is gonna make everything all better,” which was all to break us all down and take everything out of us that we were. And it nearly worked. My dad had trauma. I can remember some of the talks that we've had, and I think that a lot of those talks helped me find where I'm at today. I think of him sometimes and think that it’s no wonder he was telling me all that stuff. That's just a really, really brief summary of our tribe and how we got here.

[AJ] Thank you so much for sharing that, Sunshine. At one point, when you were telling this, I heard you take a big sigh.

[STB] Yeah, it's a lot.

[AJ] I appreciate you sharing that with us. You know, being from Minnesota, I've heard the history of Dakota removal to Crow Creek, but Ho-Chunk story hasn't been told as much. There's a long arc there and as a director of a museum, in your personal work, you've had many different roles as a teacher, as a student, as a daughter, as a grandma. How do you tell this history, especially in a public setting like the museum? It does have such a weight to it, but there is also this remarkable story of survival. I mean, the escape to this part of Nebraska is remarkable. How do you tell that story?

[STB] I, of course, leave a lot of stuff out. All of our visitors are awesome, but we get some really good questions where people really want to dig in and find out what really happened. That’s when I tell the honest truth. There's no sugarcoating what has happened to many tribes across this country. Some are completely eradicated; they're no longer here. We're fortunate enough to still be here. I would be doing my ancestors a complete disservice by not sharing that.

[AJ] Truth telling. I know Amy Lonetree, the author, has written a lot about tribal museums. I find her writing to be so interesting and she says something very similar. Truth telling is at the heart of it. I admire that work and want to dig into it a little more. As part of this truth tell, you've talked about language revitalization through HoChunk Renaissance. You've also mentioned to me, art classes. There's this cultural revitalization component. How are those two things woven together? They seem very interrelated to me.

[STB] They are very interrelated, and you can't have one without the other. I think that with my very minimal language knowledge (because I'm not a fluent speaker), I'm just trying to get the language in there. What we would do at HoChunk Renaissance is write the terms on the board, like a dress is a wāwaje, just to get those terms out there and get people to know that, not only do we make these things, but this is what they’re called. HoChunk Renaissance also has their language classes and, no matter how many times I take them or sit in on them, I always learn something new. There's always so much more to learn. Like I said, it’s a race against the clock to learn all this, share it, and be comfortable sharing it. I know that in some of my work, I'm hesitant because I always think of myself as a student. I have to get past that hesitancy to be able to show others, you know, “Let's try this. We may mess up, but let's keep going because of what our people did.” I want my grandchildren to have that opportunity as well and have that knowledge. So, my little guy speaks as much Ho-Chunk as I do. He probably knows more. And my children do as well. That's in our home.

[AJ] And how does the museum as a physical site work with these programs? I very rarely in the US Indigenous languages in galleries. I think this is more common in museums and galleries in Canada. I'm curious to know how language comes to life in this space of the museum, even if it's behind the scenes, in storage, or during programs. How does that intersect with the museum?

[STB] Everything that we have here is labeled in English and in our language. We talk about our clans as well in English, and in our language, which is Ho-Chunk. What little I know, we try to share. There’s a passport program going on right now where kids come up, to various programs and it's all about collaborating. If this program is doing something, let's throw some culture and language in there as well, and be open to that throughout our entire community. If you look at the bigger picture, the language and culture component can completely be thrown in everywhere, in every aspect of our lives, no matter how little, or how much, you know. It’s all up to us and we have to work, all of us together as a community, to do this and revitalize the culture, our language, our kinship systems, everything. It's who we are at our very core.

[AJ] Maybe that's a good point to transition into talking about cultural revitalization, especially through art, but also dealing with the histories of removal and the repatriation of human remains of ancestors. For listeners who aren't familiar with NAGPRA, that stands for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. This is just some language I've taken from the website that I'll read.

“Since 1990, federal law has provided for the repatriation and disposition of certain Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. By enacting NAGPRA, Congress recognized that human remains of any ancestry must at all times be treated with dignity and respect.”

So that's, that's a nutshell summary of your role as the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer. So, I'll start there and maybe you can tell us what that role looks like, because you're a really important person who's actually engaging with federal law to get things repatriated to the Tribe. What does that look like? How does this intersect with some of the museum's goals and maybe your broader goals of cultural revitalization and of truth telling?

[STB] Like you said, NAGPRA in a very small nutshell, basically requires federal agencies and other institutions that receive federal funds--museums, universities, state, even local governments--if they have items, they need to repatriate or transfer those human remains, and that begins by consulting with tribes and descendants.

Part of that is the protection of our people. It's really hard to explain. Protecting and planning for the human remains to be brought home. I know that when people think about human remains and however many years ago that was, how do we know for sure where that what tribe that person belongs to? They have to reach out to all the tribes that were in that area, or could have been in that area, and then we identify ourselves as an interested party, and it's kind of a long process. It depends on how many tribes are interested. Then we have to do meetings, and talk about it, and go through identifying and listing, what remains they have. It's not just human remains, it's funerary objects, and things that were buried with the person. Then, getting all those inventories, and the summaries, and everything from the museums, universities. I'm working with a few universities right now. And then, the tribes themselves decide what we want to do with them. We want to return them on their journeys back home, before they were disrupted. That's, kind of in a nutshell, what we do for that part.

Repatriation, you know, we hear this word a lot. The definition is “the act or process of restoring or returning someone or something to the country of origin.” For me, that's what I do. I try to bring our objects home. A lot of the items that are out there are not just human remains, or objects buried with them, but also our artwork is out there. What NAGPRA doesn’t reach is private collections. In private collections, people just have this stuff. We’ve been fortunate to have some people reach out to us and say, “Hey, my grandparent just passed away and we found this, and it says it's from your tribe.” I've had those items come home, as well. I think with this new age, and the younger people coming in and seeing what happened, knowing it was wrong, and saying, “Maybe my grandparents should not have this stuff.” And when they pass away, they want to return it. We really appreciate all the people who do that across the board because that is where those objects belong, with us.

[AJ] So is that the basis of the DeCora Museum's collection? You mentioned a few repatriations. Are some of the items in the collection also from families within the communities?

[STB] Yes. Some of them are from families within the communities. They've donated some things. And it's not just artwork. It's photographs, and newspaper clippings, and stuff like that too. We have a wide variety of items. We have dolls; we have our beadwork; bandolier bags; we just commissioned someone last year for a war club. That's a really beautiful addition to our museum.

We have someone commissioned now to do a painting of the Winnebago Navy. I don't know if you are familiar with that, but in the 1970s, there was Reuben Snake, Louis Larose, and others. I don't know if you know where our casino is, but it's on the Iowa side now. Our treaty states that our reservation goes along, as far as the river, but because the Army Corps of Engineers unfortunately did a lot of harm to our river, it only goes one way now. But Missouri River used to be wild and out there. It was like a wetland here. So we, in the 70s wanted that land back, which is now in Iowa, but they wanted to keep us on this side of the Missouri River. If the Army Corps of Engineers had not done what they did to the river, the river would be way over in Iowa. And so, that's the land that we got back in the 70s. So, we actually have someone commissioned to do a painting, and they'll be talking to the elders that were alive then. I think that's going to be an awesome addition to our collection here. It's not all repatriated things. We're trying to get our artists working, and keep them working, and it's not just painting. People think just art is painting and drawing, but it's creating our dresses, it's our beadwork, it's the earrings that I have on, it's my necklaces, what goes in our hair, shirts, clothing, everything.

[AJ] That's so cool that those commissions are happening, especially to tell the story of the Army Corps of Engineers and the destruction of the Missouri River. Through the dams and channelization, they've totally altered the river. I didn't realize the tribe had gotten some of that land back in the 70s. That's important to commemorate. I've seen some of your commissions, one by Henry Payer.

[STB] He's actually the one working on the Winnebago Navy. That's my nephew. I'm just so proud of him.

[AJ] He does such great work across many different mediums.

You mentioned to me too that you're doing appliqué courses. Tell us more about that. I just think it's so awesome to have art courses affiliated with an institution, to show that collections aren't static. that they’re very fluid, and you can keep people interested in wanting to learn.

[STB] They’re not static. They’re very fluid and can help keep people interested in wanting to learn.

We are just finishing up our appliqué classes. It was Appliqué 1, 2, and 3. Appliqué is hand sewn designs on dresses and shirts and shawls. Appliqué 1 was just a small one. We made a potholder, got our stitching down, and that type of thing. We had about 20 participants and they made it all the way through all the classes. The next one was a pillow. We hand-stitched a pillowcase and made a pillow. And then the last one, which is what I'm actually still working on, is the shawl. Our shawl, when somebody says, “shawl,” they imagine the fringes hanging down, but our shawls didn't look like that. They just had the ribbon work on them without the fringes hanging. That was our Appliqué 1, 2, and 3 and we had such a great response from our ladies that were in there. We got a group of them in a chat box. If somebody has a problem, all the ladies will get in there and help them try to figure it out and we meet in the evenings, which works for all of us, because we all work. It's great. The next one that we have coming up is going to be our clip and fold moccasins, which is basically weaving with fabric, and then placing that on to the moccasins creating a design.

[AJ] That's so cool. What is the age level of interest for taking classes?

[STB] right now we have a lot of, I would say, 30-year-olds or older. There's another program reaching out to up eight-year-olds and I think that starts next week. Like I said earlier, it takes a community to get all this going and have various classes here. The unfortunate part of all this is how much the supplies cost. We’re fortunate enough to be able to collaborate with Little Priest Tribal College in their Community Education program so all the supplies that people need are bought for them. That helps people come in as well because, you know, just because some people can afford, doesn’t mean everybody can. And that shouldn't be--this gate of learning. Like, “Oh, you can't learn because you can't afford it.” No. I don't want it to be like that. I want you to come in, and learn, and share, and do what you can. Ultimately, we're trying to save our culture. We're trying to save our language. You can't let something as trivial as money get in the way of that. If we can, we buy the supplies. If we can't, we figure it out and collaborate with others. Thankfully, a lot of other people see what I see and want to revitalize, so we try our best to work together and provide these items for our students and get them learning. If you teach somebody, a mother, or a father, they're going to take that home and teach their kids. Then it just grows from there, you know. It's planting seeds.

[AJ] Yeah, it's really important work. To bring the conversation full circle, I want to talk about sovereignty, and whether you see your museum, or tribal museums in general, as sovereign spaces. What does exercising sovereignty look like in an art context? A historical context? Those are, of course, interrelated, but how are the revitalization programs you've been talking about an expression of sovereignty?

[STB] If we jump into sovereignty, it's the discussion about what sovereign is and what a sovereign nation is. I tell my students that it’s basically a country within a country. All of our tribes, the 450 recognized tribes in the US, are all little countries throughout this big country, which is the United States, and as sovereign nations, they govern themselves. We have our own constitutions. We have the same powers as other sovereign nations, federal, and state governments to handle our own internal affairs. So that's kind of a little bit about what sovereignty means and as a nation, what it is to our reservations and our tribes.

I think that there's a difference between tribal museums and collecting institutions, the museums that you've gone to in big cities. Those, to me, are just collectors. There's a purpose of revitalization and finding what was taken from us. That's a big part of what I do, finding our items out there. I do a lot of praying about it so that I can find things and bring them home to us. When I bring those items home that were taken from us, there's this beauty in them. Beauty in our art and beauty in the fact that my ancestors’ hands made this item and, from that, learning and knowing in our heart. Right now, a lot of us are colonized, which is sad. Learning and knowing and seeing our artwork and things that our ancestors have made, and then realizing that that my people made that, and I'm very capable of doing that, my students are very capable of making that, helps us preserve our cultural across the board, from language, to arts, to different things. Then, they can then be the teachers after I'm gone.

Within the community, the role that we play is to make sure our tribal members are comfortable asking questions, are comfortable learning, and wanting to learn with no shame. Earlier, I talked about this unfortunate thing that goes on throughout all tribes, through the lateral oppression and bullying like, “Hey, you don't know that. Or, how do you know? That's not how my grandma did it.” That shame is within our communities. We have to push that aside and give them a safe space to learn and say, “Hey, I may not know this.” I always tell them, “I don't know, but I will try my best to learn and teach you as well.” And we're all learning and teaching together and learning from each other. I think that once you get people with those same ambitions, that same type of mind frame that we need to push everything aside and revitalize our culture, no matter what, we forget our egos. We just need to come in and work. My elders tell us is that we shouldn't be creating if we have bad thoughts. You always have to go in with a good heart when you're creating. When I start focusing on bad things, or if I'm stressed out, it comes out in my artwork. So, then I have to start over. It gives me gives me this sense that that I need to let go of all that worry and just focus on what I'm trying to create because I want good feelings to come into this. Whoever I'm giving this to, I want them to know that this comes with good feelings and good prayers to pass on to other people. We really try our best to do that and teach that as well. It comes out in the art.

[AJ] Yeah, it does. You're putting all this work into courses, into storytelling, into truth telling, into your kids, your grandkids, and thinking about the next generations. What does your dream institution, or tribal museum, or revitalization program look like 20 or 30 years out? What does that look like to you?

[STB] We do have a nice building right now, but it's just not fit for what we need. As you know, you work in museums as well, we really need something that is going to hold artifacts safely, like temperature and security wise, to make sure these items I'm holding in this museum right now are going to be okay a few generations down the road. With all these items that we have, even after I'm gone, people will still be learning from them. I would really love to have a space big enough to share our history, because we have a really rich history of artistic traditions. There was artwork in everything we did. If you look at the whole picture, there was art, there was science--we had science within our history and in our beliefs. Like how we use a calendar. Simple things that we take for granted now where I can just look at a calendar and know the date and time, but it used to not be that way. It used to be that you looked at the stars and different seasons and knew what month it was. We used to have 13-month calendars, rather than the 12-month that we have now. I would really love to have this all together in this big space with enough room for classes. I just think that is what my dream Museum is. Space for people and classes, like a big welcoming family. Come in and learn and look at this stuff and try to recreate it and do better. Be better. Make our ancestors proud. They were nearly eradicated, and you hold the key to them and bringing their past back to life.

[AJ] That's beautiful. I want this to happen. The DeCora Museum is doing so many wonderful things. I want to encourage everybody who's listening and who is reading this to go visit because there's a lot to learn there. Like you said, there's a very rich history. But yes, I could see a much bigger space.

[STB] I could see a much bigger space. I see classrooms upstairs, and kids, and people wanting to learn. To me, that's what I want. That's what I want for this museum--an active space, active learning, and a welcoming, safe space, for anyone. If there was someone who came, say they were part of the relocation era, and they just came home and wanted to learn all this stuff, I would want them to have a safe space to do that in without judgment or someone telling them they’re not doing things right. That has happened to me, you know, in my learning path, on my way to where I'm at today. I still have a ton of learning to do but I've had those putdowns and it doesn't feel good. It makes you want to quit and ask, “What am I doing this for?” But ultimately, we're doing it to save our people. That's the bottom line, we need to save our people.

[AJ] That's an important mission statement and so much hard work. I just wanted to ask if there's anything else you’d like to share.

[STB] Well, I sent you and Peter, a little preview of our history video. It's called the History of the Hōcąk Nīšoc Haci. It’s entered in the American Indian Film Festival. We're crossing our fingers with that and really hoping. We'll see where it goes. Either way, I am so proud of that. My museum curator, Eben Crawford, and Garan Coons, we all worked really hard. So did everyone who helped with that video. It's kind of like what I talked about, but a little deeper into our history and how we came to be where we are today. Even just watching the preview earlier, before I sent it to you guys, I was getting fired up about it.

Classes will continue too. We're trying to find more classes for items that we have in the museum and that aren't really taught. It’s a tough road to find people who hold that knowledge, who are willing to come teach. That's also a barrier to us as people. These knowledge holders, some of them, they are not willing to share, or they are reluctant because they say they don't know enough to share but say they’re the last one left. If they pass away tomorrow, then that knowledge is gone with them. It's really tough to get that idea through to see past us.

You know, I'm an introvert at heart, and it takes a lot for me to stand up and, talk, or share my thoughts. I'm an observer, but I think that there's so much important work to be done, and so much that needs to be shared in such a little time, that I have to crawl out of my shell and be able to share that with everybody and talk to people and try to bring my ancestors home or try to bring our artifacts home. That's what helps me get out of my shell a little bit and do the work that I do.

[AJ] Well, thanks for getting out of your shell today. Thanks for sharing all of this with us. Thank you so much and I look forward to future conversations!

Sunshine Thomas-Bear is the Director of the Angel DeCora Memorial Museum and Research Center in Winnebago, Nebraska. She is also the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO) for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. In both capacities, she works to revitalize and invigorate cultural lifeways of the Ho-Chunk people. Visit the Angel DeCora Memorial Museum and Research Center in person and follow, subscribe, and like on Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook.

Annika Johnson is Associate Curator of Native American Art at the Joslyn Art Museum where she is developing installations, programming, and research initiatives in collaboration with Indigenous communities. Her research and curatorial projects examine nineteenth-century Native American art and exchange with Euro-Americans, as well as contemporary artistic and activist engagements with the histories and ongoing processes of colonization. Annika received her PhD in art history from the University of Pittsburgh in 2019 and grew up in Minnesota, Dakota homelands called Mni Sota Makoce.