AC Interview | Steve Tamayo

We recently asked Amplify’s 2020 Indigenous American Artist Support Grant recipient, Steve Tamayo, if he would share some of his thoughts about what it means to cultivate creative activist practices in rural spaces and how those practices connect revitalizing and preserving indigenous cultural knowledge to ecological justice. Listen to the interview below or, if you’re on the go, on Amplify’s Anchor page and share your thoughts in the comments section.

Transcription

Interviewee: Steve Tamayo

Interviewer: Peter Fankhauser, Program Director, Amplify Arts

Date of Interview: May 18, 2020

List of Acronyms: ST = Steve Tamayo, PF = Peter Fankhauser

[PF] You're listening to Amplify Arts’ Alternate Currents interview series. Alternate Currents opens space for conversation discussion and action around national and international issues in the arts that have a profound impact at the local level. This interview series is just one part of the alternate currents blog, a dedicated online resource linking readers to topical articles, interviews, and critical writing that shine a spotlight on artists led-policy platforms, cross-sector partnerships, and artist-driven community change. Visit often and join the conversation at www.amplifyarts.org/alternate-currents.

We recently asked Amplify’s 2020 Indigenous American Artist Support Grant recipient, Steve Tamayo, if he would share some of his thoughts about what it means to cultivate creative practices in rural spaces and how those practices connect revitalizing and preserving indigenous cultural knowledge to ecological justice.

[ST] My name is Steve Tamayo. I’m a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in my language we identify ourselves as the Sičhą́ǧú Lakȟóta. My family comes from a small community called Milk’s Camp on the Rosebud reservation. I was born and raised here [Omaha, NE] but my mother grew up in that area and so policies carried out by the United States Government, this is how she was able to make her way off the reservation to the Omaha area because of the relocation act of 1940’s and 1950’s. After she made her way out of the boarding school, she had to go find her siblings. My aunts all left letters at the farmers, the neighbors, and so that's how they were able to find each other after the boarding school system.

I heard these stories of atrocities at the boarding schools and the effect that it had on Indigenous People and so I was kind of fascinated by just being Indigenous. But what do you do with that, you know? I always asked her all kinds of questions and it was quite amazing for her to be able to actually retain as much as [she did] because of what she had to endure in the boarding school system, residential schools. She kind of filled me in as much as possible and then, pretty much after I made my way out of the military, I took off up to Rosebud just to learn, to focus more on this way of being. While I was here in the Omaha area, I was fortunate enough to come across some Elders here in the community that had different talents, had different interests, and so I was seeking out all these different elders because I wanted to learn as much as possible. Understanding that, and the importance of retaining these cultural teachings, kind of started my journey.

Then I had twin girls who wanted to dance. I was a single and dad didn't really know how to help them within that powwow circuit, in that circle. So once again, I went to my mother and was asking her this and that, but that information was taken from her. We had connections up North, so I would go and seek and find family members in our community able to help us but I wanted to learn more. That's when I started seeking all the Elders that knew this way of life. That's kind of the path, I guess, and the pathways, which led me to finding these specific Elders. When I moved to Rosebud Reservation, it was about me taking the language classes offered on my reservation at Sinté Gleska University. My mother was able to retain some of that information, some of the language, but they took her when she was four- or five-years-old and it was prohibited--they weren't allowed to speak the Lakȟóta language (Lakȟótiyapi) so she lost a lot of that information. When they took her, she didn't speak a lot of English anyway, you know, and that's how powerful our language actually is. She was able to retain that you know even 15 years later. Understanding that, whenever I had questions, of course she was the first one I would seek, but then I moved to the reservation and I started taking classes and one of the first classes I took was a Lakȟóta language class, just basic 101.

There, I wrote this essay and handed it over to my language instructor at that time, and in it I told him that I know how to make headdresses and bustles and do this feather work that I was able to learn from the Elders in the Omaha community. So they're like, “Oh my gosh, nobody knows how to make these specific headdresses.” They're called headroach headdresses . I started writing lesson plans and documenting this and creating my own curriculum. With the help of the instructors at Sinté Gleska (Spotted Tail) University on my reservation, they kind of guided me into this way of being and documenting and creating lesson plans that incorporate the language as well. When I was on my reservation, I was teaching in English and Lakȟóta and that just blew me away, to have access to the instructors at that time. Most of my teachers now have passed on and I think I have three Elders left that I still rely on because of their cultural knowledge. As time goes by, that's what I'm trying to do.

Now, as you know, I'm making a rawhide container. These are just containers that we would store feathers or food or clothing in, whatever you need, just like containers today. The only materials that we had back in the day were rawhide and deerskins to use as lace and bind up the rawhide after I punch the holes, or drill the holes today. This is how our boxes are made. I'm [working] to finish seven containers, but we always make them in pairs, so I have to make fourteen rawhide containers. I've used six cowhides so far and two deer hides to bind all these containers up. After I'm done making them this week, then I have to create the lesson plans that coincide with them and explain what is the purpose and function of this. Then last, is explaining the symbology, the symbols that exist on the containers. This was typically, back in the day, a woman's art form to make the rawhide containers that they needed within her own lodge. I'll put that into my lesson plans and make a video of each container so when I ship it to our NICE students and to the teachers, they understand what is the purpose and function and usage of this specific container. Then, when they look at it, you know, “What is the symbology?” I incorporate that. I incorporate numerology and design elements because everything has to be specific. Then, I incorporate the color concept. These rawhide containers are very specific to specific regions and specific tribes. These are primarily Lakȟóta / Dakȟóta rawhide containers but if I was to make containers for the Umóⁿhoⁿ or the Winnebago, the Ho-Chunk (Hoocągra) Nations they would have a different design concept that is Tribe-specific.

Being the cultural specialist for the NICE program, the Native Indigenous Centered Education, this is what my job entails: explaining the symbology of the plains and the tribes within, specifically the four tribes of Nebraska. Once you get into how complex our societies and our clanship are--the symbology; the color concepts; and numerology; the ten different regions; when I talk about moccasins, what region am I speaking of--this gets really complicated. To be able to be adjunct at UNO and to teach at Metropolitan Community College, it’s amazing for me to be able to pass on this information because I love studio art classes. I love hands-on and the only way to truly understand this way of being is just to get your hands dirty. There's a lot of people that are well-read but what's that book gonna do when you have a live Buffalo in front of you, you know what I mean? How do you process it and how do you tan the hide and make the bones into the tools and games and everything that you need. This is what I've been able to bring to the table and so once again, it's a nice time, it's the right time.

During my little quarantine time period right now, the best way for me to spend my time here is for documentation and to create as much as possible. It’ll benefit many generations down the road with our technology that we have access to today. I have access to the Joslyn [Art] Museum now because of Annika [Johnson, Associate Curator of Native American Art at the Joslyn Art Museum], who is a gift to all of us in the city. I'm really happy that she's here. The first thing I told her, or asked her, is if I could get into the vault, because I was trying to get into the vault for the last 25 years, and she's like, “Sure!” So she opened it up, not only to me but to my students as well, because I want them to see the technique that was utilized back in the day and what’s different and to look at the materials because it all has a story. This is, for us, you know incorporating our creation stories and all of our stories of our designs and color concepts, it's more meaningful. For our kids to see works of even their relatives, great-grandparents, great-great-great-grandparents, I'm just like “this is amazing.”

There's not many of us that know how to make these items anymore. Even when I scrape out my buffalo hides you know to brain tan them, it's a process of scraping off the membranes, the epidermis, the awful, the fat, the meat, everything off of that hide, and stretching the collagen fibers when I frame up my buffalos on their frames to open up those pores. I still use that old process of brain tanning, so I cook up the brains, the fat, the water, and that's how I break down those enzymes and everything and those collagen fibers. It's a process that many people just don't do anymore. I think I'm the only brain tanner in Omaha.

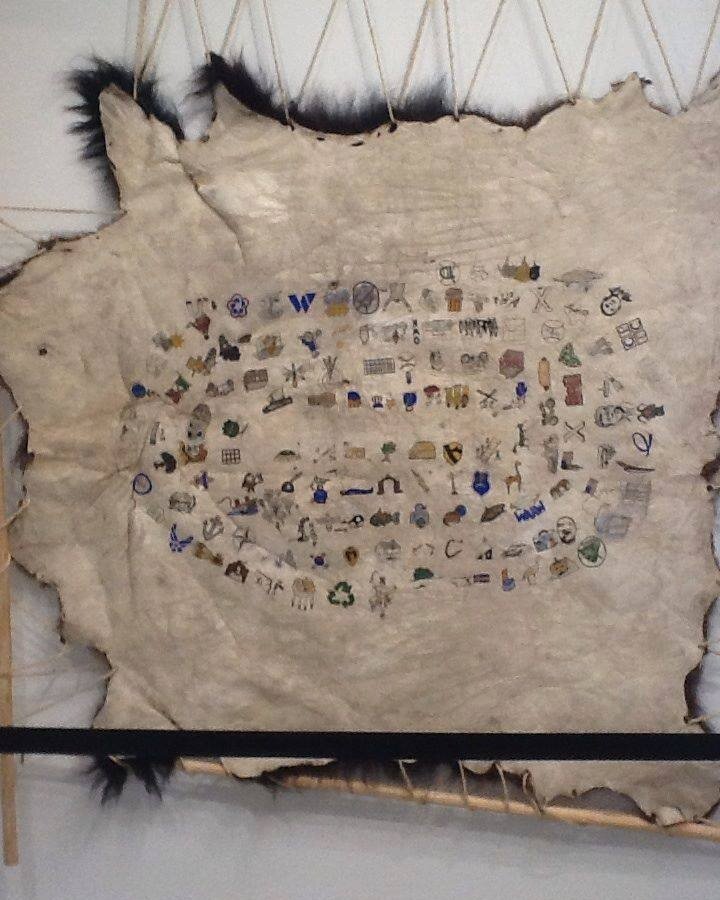

Fort Omaha Winter Count, 2012, brain-tanned buffalo hide and hide glue paint. 4’x6’. Hide brain-tanned by Steve Tamayo and painted by Tamayo and class of Native American Art History students at MCC.

Pesa (headroach), wool yard, porcupine guard hair, deer hair, sinew. 30”x6”x14”. Worn by traditional male powwow dancers.

Look what's happening today because of the pandemic, because of what's going on in the packing houses. They’re getting hit hard because of that confined space. Understanding that, we just purchased five hogs last week because the farmers can't afford to feed the Hogs anymore. I mean, it's getting to that point. So I'm like “Well, I know how to butcher.” People have been picking me up left and right [asking], “Can you show us this and that?” I had my own little team of butchers and we were able to harvest at least five of the hogs. In a week or two, we're going to be butchering cattle next and in the fall time, I'm gonna target the buffalo. So there's a timeline for everything and not only am I harvesting all this different type of meat, but I'm gonna start harvesting a lot of our plants and so that'll be next.

In all of the Indigenous languages that exist, animal doesn't exist--that word. We acknowledge, we say “wamákȟaškaŋ.” These are the beings that roam the earth. That can be the trees and the plants and how they pollinate and there’s constant movement. That's how important a different indigenous mindset that we're trying to pass on to our generation is because that was taken away from us. What they had to endure in the boarding schools, this self-identity was just totally wiped away. That concept of understanding the importance of when we say “táku kiŋ oyásʼiŋ,” is that we are related to everything that exists if it lives and breathes. That's a plant, it's our winged relative, it's our water relatives, our four-legged relatives and so we identify them as relatives; even the plant nation, they're our relatives. So before we can go harvest, this is one thing I pass on to to my kids. For the last few years, I've taken students from OPS to my reservation and before we can harvest, we have to pray. We have to ask forgiveness because we're gonna take the lives of these plants. Even when we have Sundance and we take that tree down, there's a ceremony. This is something we pass on: how interconnected we totally are to everything that exists, lives, and breathes, if it needs water.

Look how important water actually is. When I talk about sacredness, you know, what is truly sacred to us? It's the food that we need to nourish our bodies. That's truly sacred. Don't waste food. This is something we try to pass on. Back home, there's a lot of places where you don't want to bring water balloons. We don't play in the water like that. You want to play in the water, then jump in the creek, jump in the rivers. Look how simple that is. If you use these water balloons, what if the birds eat them, you know what I mean? Look what we've done to the earth.

This pandemic, this is an awakening. Indigenous people have been affected with diabetes and we have heart problems and all these different diseases that never existed amongst our people. Now we're dealing with it and it's new to us but it's had an impact, just like cancer. Once again, look at our reservations what they did. What did the government do with waste, nuclear waste? They put it on our lands. There are reasons why our waters been contaminated [by] what they brought there and what they've unearthed. This is one thing that that we have to deal with day in, day out that people don't understand. On my reservation, there's 40,000 plus people there but we only have one hospital. It has 22 beds and I know that we have [only] two or three ventilators. If [the pandemic] hits our reservation, because it's on lockdown right now, people don't understand the true impact it would have on that rural setting. The nearest hospital, besides ours, is hundreds of miles away. How are you gonna get these people there? That's how scary it is.

What's hit the Diné, the Navajo Nation, they're always telling everybody how important it is to wash your hands. How do you wash your hands when you don't have plumbing? Half that reservation, they don't have access to water. They have to go to the wells and fill up their containers and bring them back to their homesteads. Once you bring these things up to people, they're like, “What do you mean they don't have water?” I know people in Rosebud that don't have water, don't have electricity, still have dirt floors. People don't understand what exists on our Reservations still today and how hard it is to live there. That's why it has the impact that it does. I'm glad they're on lockdown, you know. Even after they open it up, I'm still gonna allow time. I can go in with a small little crew and harvest what I need and document and get out of there without being around anybody. That's how isolated my community is. I can take all the backroads in and document and then get out of there so I don't harm anybody and I'm very careful about how much I harvest because we have to share.

I've spent the last 20 plus years on the Rosewood Reservation and so I know where all my plants are there. I don't know where they are here [in Omaha]. It's gonna take me a long time just to walk. So I plan on walking a couple hundred miles up and down the [Missouri] river on both sides because I'm looking for specific plants. The plants that I'm looking for are gonna serve the the medicinal. Once I find these medicines, what type of medicine is it? Is it the roots or the plants or the leaves, the stems and when is it most potent? There's specific times to harvest our plants for medicinal purposes, but also for spiritual purposes, and the edibles and then the drinkables. It's gonna take me a while and so I'm putting together a team of people just to go hiking and go find all these different plants that we can use for those 4 specific purposes.

Being an Indigenous artist, I do a lot of work with the KXL, Bold Nebraska, fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline, understanding how important that is. They called upon me. I was just kind of minding my own business on my Reservation when Bold Nebraska found us. They wanted specific art to identify Indigenous people. Today it's an alliance. They called it the “Cowboy Indian Alliance.” I thought it was kind of cliché at first, but when we actually all got together, I was like, “Hey, this is really cool,” because it encompassed all of our farmers, our ranchers, our green groups and passing this on to what we call the the climate kids. We're bringing an awareness to the next generation--these kids from from all of these different groups have been with us.

It started out with a lot of our leaders of faith and the power of prayer and our mission was to actually protect the [Ogallala] Aquifer, which goes up into the Dakotas all the way down to Texas. People don't know about that. That's our water source you know for 10 to 15 million people, not including our crops and our livestock. All these pipelines go in and underneath the water system, like the TransCanada, KXL. That pipeline and that tar sands were never gonna benefit the United States. This is an awareness that we're bringing. It's the tar sands from Canada, they're building these pipelines to a refinery in Illinois. They've been going underneath the Missouri River. This started in 2008 with the KXL. In 2010, that's when Jane Kleeb founded Bold Nebraska and she's the one that pretty much single-handedly united all these different organizations. We've been backing her for a long time. Jane is the one who found me and asked me if I could help her create art for the protest for the pipeline. I've been to DC with her 3 times already protesting and marching and bringing an awareness. Of course, you know, we have the hecklers and the non-believers and all these people even here in Nebraska and they don't see the importance of our water system.

Because of the KXL and my involvement there, I was kind of summoned to go up to Standing Rock. That was life-changing. The people who made their way there, over a million people actually made their way to Standing Rock on both sides of the Cannonball River (Íŋyaŋwakağapi Wakpá). My job and responsibility there was to be an instructor, a teacher at a school that we created because there were just kids everywhere, thousands of kids. So we started our own school there because their parents became the people on the frontline. Our school was actually like a safe haven and we were the caretakers of all these kids. With my background in teaching and incorporating this educational component of revitalizing and reconnecting with our ancestral teachings, I could just go in up there and partner with some of their Elders because I think I'm still a young guy. When older people come up, I let them take the floor. That's their lands; that's their territory. Of course I can go up and teach, but if they have something to say then by all means, here's the floor.

That's how I travel throughout the country. You have to be aware of who's homeland, territorial lands that you're actually on because those are specific teachings. That's how important this is. It changes everywhere you go. We are all in the lands of the Umóⁿhoⁿ people and so anytime I give presentations, I always identify the homelands of who we are standing on. If there are any Umóⁿhoⁿ people in the room, that shows a sign of respect. Once you do that, you establish that relationship because as Indigenous people, we don't have friends, we make relatives. We have a really strong kinship that exists. There were a couple little grandmas who adopted me into the Umóⁿhoⁿ Tribe, into the to their families. Because of ceremony, we call it “wótakuye,” a kinship. It's an adoption. From that time on, I became their son. I look at all of their little relatives now. Now they call me uncle, they call me grandpa because we established that relationship many, many years ago. That was my buy-in. It puts people at ease because I am very respectful of the Umóⁿhoⁿ people and their teachings and and their land base. I always acknowledge that first and foremost. Then, I look at their their designs; I look at their clothing and not only today but I look at you know archival photos. I find as many books as possible to read up on. We're not all the same, you know. There are hundreds of tribes in the United States and anytime I go anyplace, I always try to read up on the people whose ancestral lands those actually are. I'm a Lakȟóta. We are the third largest tribe in the United States, but that doesn't mean anything, you know. When I travel, I say “travel abroad” because I go into different territories. Just be mindful of that. Be mindful of who is allowed to speak. There's certain times where women aren't allowed to speak but there are certain times where the women are the true leaders of that band, that tribe. Because of European thought and philosophy, Indigenous people back in the day kind of backed off of that. The Clan Mothers are very strong and still exist today. I'm just mindful of these things.

We are not only gender specific, but age specific. Quite often, you'll hear a lot of Indigenous relatives you get up and before they start speaking, they'll say, “I want to you know look to the Elders.” We're not experts on anything, you know. That mindset is once again of European thought. That's why our clanship is so important because of roles and responsibilities and duties amongst the people. Like the Umóⁿhoⁿ, if I want a drum, I have to go to a specific Clan and ask them to make that drum. If I want a certain song, I have to go to a different Clan and ask them, like the Bird Clan. The birds in the morning at 5 o'clock, they're the ones that are harmonizing. Because of these melodies that they bring to the two-leggeds, this is how our songs were created long ago. So we follow these old traditional teachings of specific roles and responsibilities and duties.

We knew that that the pipeline was going to be coming. We've prophesied this black pipe that was gonna go underneath the ground and into the waters. When that pipeline came across our land--because they never consulted to bring that pipeline across our lands; it's federal trust land and it's about big business, it's about money--as Indigenous people, we’re standing up and [saying] we don't want that here. That pipeline that was gonna go across Standing Rock, it was going underneath their water intake but the first route was north of Bismarck and it was gonna head west and totally bypass the reservation. Nobody said anything. But then the farmers and ranchers are like, “No we don't want that pipeline on our land because it's gonna leak.” Why is it okay to leak on the Reservation? Why is it okay to leak underneath the water intake? That's what we stood up for. The KXL was started once again in 2008. Here comes both Nebraska in 2010. Then in 2015-2016, here comes Standing Rock and NODAPL. Even the name, “Dakota Access [Pipeline]”--Dakȟótas and Lakȟótas never gave you access to cross our lands--that was a slap in the face. Once they first named it and said, “This is what we're gonna do, we changed the route, we're going underneath your water intake,” that's why we had a standoff. That standoff cost billions of dollars because we stood up to the people. We stood up for the people, I should say. During this whole time, because of climate change, because of fossil fuels [there’s] been an awareness for all the people to come together to stop this.

Here's a story for the KXL that people aren't aware of. How are we gonna stop this this pipeline from coming across the the farmers’ land in Nebraska? Jane and a nice handful of people got together to brainstorm and they pulled these seeds, these historical seeds that were collected way back in 1800s from the Ponca people when they used to reside here in Nebraska. They took these seeds to the Department of Agriculture in DC. We went to DC and harvested some of these seeds, brought them back to Nebraska, and planted him with the historical significance. Today, we're calling these the sacred seeds of the Ponca. Because of that, and the historical significance [of these seeds], it stopped the pipeline from coming across that land. It was just unbelievable that they could brainstorm and and come up with these different ways and means to utilize the plants to save our water across historical lands that belonged to the Ponca before they were removed from Nebraska long ago. It still had an impact 100, 150 years later. That’s pretty powerful

#NODAPL--that Dakota Access Pipeline--that movement was actually started by the kids. I don't know if you're aware of that, or if most people are aware of that. These kids ran around the reservation up at Standing Rock. In our language, they’re members of the Húŋkpapȟa Lakȟóta. When you look at the Lakȟóta, there's seven bands. I'm one band from Rosebud, South Dakota; we are Sičhą́ǧú, the Burnt Thigh People. Húŋkpapȟa are the Guardians of the Entrance. My next-door neighbor down in Rosebud is from Pine Ridge. That's where the Oglala come from. Understanding that, on the lands of the Húŋkpapȟa, the kids ran around that Reservation and had thousands of people sign this petition to stop [the pipeline]. They wanted to take that petition to the Army Corps of Engineers and so those kids actually ran from Standing Rock all the way to Omaha, Nebraska. All along the route they were contacting the different Tribes, the different Nations, from Standing Rock to Omaha. All these different Tribes were collectively gathered to to take care of these kids when they came across the Reservations. It was a movement started by kids it just showed that they're sick of it. They wanted to stand up; they wanted to acknowledge that we're still here. They wanted their voices to be heard. That's how powerful the movement was.

They ran all the way here to Omaha and we had a huge gathering here--thousands of people. You know what those kids did and all along the route? They gathered more kids from different Reservations and all these kids ran to Omaha and then they ran and to Washington DC. Just think about how powerful that is. Those kids ran all the way from Standing Rock to Omaha, from Omaha to Washington DC, to take tens of thousands of signatures to the Army Corps of Engineers, the BIA, everything else there, the Department of the Interior. That alone acknowledges our survival, acknowledges our cultural teachings. All along, we utilized prayer. All along, it was it was based on ceremony. What happened at Standing Rock when the people stood up, it truly brought a worldwide awareness of these injustices once again. We haven't had that kind of a movement or voice since the Wounded Knee takeover in the 1970’s. For our kids to lead that, it was just amazing, just blew me away.

However we could help reinforce and be a part of that movement, that's what a million-plus people decided to do. That's why we made our ways to Standing Rock. It was a beautiful time. It was a very powerful time that I'll never forget. It put us on the map and [brought] an awareness that we are still here and of what happened to the Indigenous people. It gave us our voice, gave us this ground to stand on looking back at treaty rights and the injustices against Indigenous people of this land. For us to only be 1% of the population of the United States today, we have a very powerful voice and say so because of our Reservation lands what exists there because of mineral rights and water rights. It's time for us to stand up. This worldwide pandemic has brought an awareness of climate change and the injustices of all these fossil fuel companies and bad government decisions. People who've never heard of the Húŋkpapȟa, they know who they are nowadays because of national news. Finally, [we have] that that ground to stand on once again.

*This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Steve Tamayo draws upon his family history as a member of the Sicangu Lakota tribe. His fine arts education (BFA from Sinte Gleska University), along with his cultural upbringing, have shaped him as an artist, historian, storyteller and dancer. Steve provides activities during his residencies that include art and regalia making, drumming, powwow dance demonstrations and lectures on the history, symbolism and meaning behind the Native customs and traditions.

Steve has considerable experience developing curricula and teaching both youth and adults, including work with the Native American Advocacy Program of South Dakota, Omaha Public Schools, Minnesota Humanities Council and Metropolitan Community College of Omaha. He also leads groups of students and teachers on cultural excursions on the Rosebud reservation, introducing them to the rich culture and way of life that is slowly being revived among native communities. He is a past Governor’s Heritage Art Award recipient, an honor bestowed for his contributions in the arts and Native American culture.

Tamayo has had work exhibited at The National Museum of the American Indian, in Washington, DC, The Kaneko in Omaha, NE, The Great Plains Museum in Lincoln, NE, RNG Gallery in Council Bluffs, IA. His most recent work included painting buffalo robes and set design for Willie Nelson and Neil Young on the occasion of their concert for Bold Nebraska in Neligh, NE.