Holly Łukasiewicz | More Than Flowers

A flower installation created by District 2 Floral Studio in a garbage bin in the Old Market - Omaha, NE (May 2021). This was done to bring a fresh perspective on urban environments - What do we value? Where is value placed? How is that value expressed? All flowers sourced locally.

Growing in Reciprocity

Full transparency, I don’t identify as a florist in the traditional sense of the word. ‘Flower artist’ would probably most closely describe the type of creative practice I find myself steeped in these days. I am a creator, curator and independent designer as District 2 Floral Studio, which I think of as a floral shop without walls.

For me, common daily activities include: Slinging water-filled vessels with flowers, bundling flowers for others to hold. Creating mood boards, scheduling, sourcing and processing flowers. Arranging flowers for others to wear. Listening to customers talk about their vision and then creating with flowers to help them experience that vision. Gathering pre-loved vessels. Meeting other local growers. Researching sustainable practices. Learning about local and “invasive” flora. Growing a community of sustainable growers, farmers – my flower people. Culminating in flowers to adorn a door, a home, a place. Installations in museums, homes, parks, even garbage cans.

My art supplies come from the expansive Great Plains. I create art with seasonal perennial and annual plants, and prairie grasses. My goal is to source them locally and use seasonal plants from local urban farms, specialty-cut flower farms, and yard gardens – these are my art supply stores. During our growing off-season I source American-grown flowers from a local flower wholesaler.

A flower installation by District 2 Floral Studio within Leslie Iwai’s "community" Sounding Stone sculpture, Omaha, NE (Feb. 2021). This is part of a series of installations created by rescuing 100s of landfill-bound roses that were otherwise being discarded (leftover from Valentine's Day at a chain big-box florist).

I see the Earth as the ultimate provider for these materials, and I am grateful for the interconnectedness of my proximal environmental ecosystem. The nature which surrounds me dictates my supplies. As an act of reciprocity, my intent is to follow their lead. I also see florists as artists. This line of creative practice offers a unique opportunity to explore ephemerality within a creative practice. Knowing a florist’s supplies come directly from our Earth – water and flora – an ecologically-sensitive design practice has the potential to guide creative choices by weighing their impacts on environmental ecosystems.

When I worked in a big-box, chain florist retailer, I was shocked by the disconnection from ecologically-sensitive practices and the amount of flora, single-use plastic waste and toxicity involved – throwing away hundreds of roses each week because they were deemed “too old” after 3 days, for example. It precipitated a perceptual shift toward observing the beauty imperfection and waste hold.

When I began taking floral design courses to learn more about it as a line of work, my fellow students and I were regularly given a block of green, single-use plastic foam as the common design base for each piece. Our courses offered no class discussion around its impact on the environment and the waste it creates. When I posed questions about alternatives, one instructor let me supply my own foam alternatives; one disregarded my inquiries.

Using these foam blocks was an observation in structural design biases that became common practice in the 1950s, most of which are still deemed acceptable with little regard for the harmful impacts foam has on waterways and the living beings who inhabit the water. Too often, harmful design practices and material use are overlooked in favor of creative freedom. In the case of flowers, Becky Feasby of Prairie Girl Flowers and graduate student in sustainability at Harvard, describes it as “hiding behind the pretty,” or behind trendy aesthetics. An ecologically sensitive design practice works consciously to bridge the gap between what’s interesting, what’s beautiful, and what’s ethical. I call this “impact-conscious,” because this way of working centers well-researched design choices that thoughtfully weigh their impacts on environmental ecosystems. And it’s at the center of my small business and art practice.

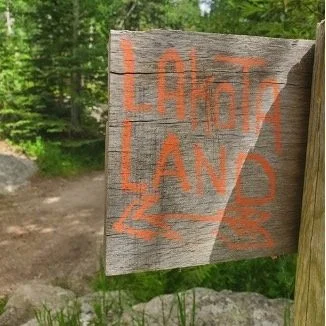

Hand scribed lettering that reads “Lakota Land” found on a sign at Black Elk Peak, Black Hills, South Dakota, acknowledging the history of forced removal of Indigenous tribes from their sacred homelands (July 2022).

I left the big-box chain florist and began focusing on designs steeped in a values-based practice that felt honest and holistic – for myself, for others, and for the Earth. I’m guided by the wisdom and writings of Indigenous botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and Indigenous arts educator, Emi Aguilar to better understand how reciprocity enters my work. My practice is free from the use of foam as a structural element, free from the use of single-use plastic items (such as card picks and flower wraps), free from the use of bleach, synthetic dyes, or paints. I compost unused foliage and stems. I use natural fiber ties that are compostable. I source vessels from resale shops to lessen waste consumption. I source as locally as possible with the seasons, and from local farmers and other land stewards. I research sustainable approaches to floral design, and take classes online that offer instruction in foam and plastic-free alternatives. They’ve helped me connect with mentors whose knowledge and generosity continue to shape my practice. (I reference many of them throughout this post!)

My guides and teachers inspire me to share a portion of District 2 Floral Studio’s sales each month with an organization rooted in social justice and community-growing. I see this as a small way to practice a form of reparation and Landback. Cultivating an ecologically-sensitive design practice grounded in intersectional environmentalism has helped me understand the larger perceptual shifts that accompany small gestures of reciprocity.

Growing a Movement

In many ways, flowers are my activism. Their intersection with justice, equity, economics, and environmentalism has helped me understand their interconnectedness. For that, I am grateful to them. They’ve helped me recognize that social and environmental justice are intertwined and that environmental advocacy which disregards this connection is harmful and incomplete.

This movement toward intersectional environmentalism focuses on achieving climate justice, amplifying historically excluded voices, and approaching environmental education policy and activism with equity, inclusion, and restorative justice in mind (Baker, Martinez 2022). To understand the scope of intersectional environmentalism in the context of an ecologically-sensitive design practice, I think about how I source flowers. (This could also be applied to art materials in other practices.)

This insignia on floral packaging in retail shops certifies the flowers were domestically-grown under ethical working conditions.

My relationship with flora is inspired by the Slow Flowers Movement. Similar to the Slow Food Movement – which formed in response to fast food chains and a growing disconnect between where our food comes from, who grows it, how it is prepared, and the decline of eating meals with others – the Slow Flowers Movement is a response to the past 30 years of United States policy changes that created an influx of dependency upon foreign-grown flowers. It is a movement towards knowing where your flowers are grown, your farmer’s name, the ethical conditions of the workers, and types of chemicals used (if any).

Here’s a little history on how we got here. Because of the Andean Trade Preference Act of 1991 voted into law during the H.W. Bush administration's "war on drugs" campaign, the United States began to offer South American farmers tax-free incentives to grow alternative crops, such as flowers, instead of coca, the plant from which cocaine is derived. This created a lopsided economy within the industry and increased American reliance on foreign florals.

Today, only 20% of flowers sold in the United States are actually grown here. Most flowers we see at supermarkets are commodity crops flown in from "big ag" factory farms in South America, Africa, or Europe whose working conditions are notoriously opaque and the impact on the environment just as muddy. The lack of safety regulations for growers working on these farms create conditions under which the land and worker are abused, disproportionately affecting Indigenous, femme-identifying communities in the Global South. Often, workers are not paid a livable wage. We are seeing this play out in Ecuador, with recent strikes by Indigenous land workers, bringing to light the extreme social inequity, fueled by inflation of their food and gas prices.

Given that 44% of all flowers grown in Ecuador are exported to the United States, this strike puts pressure on the floral industry in America. Farms cannot send flora due to road blockages in Ecuador strike areas, therefore U.S. flower wholesalers are not receiving inventory, making it challenging for florists/designers to have access to flora (if there is a reliance on imported flora). It goes beyond your grocery store florist running out of roses; it’s an issue of people and planet.

Buckets of fresh flowers sourced locally from Big Muddy Urban Farm (Omaha, NE), and Hen and the Hawk Flower Farm, a specialty-cut flower farm in Fort Calhoun, NE. (Left photo by Kamrin Baker Creative.)

Domestically-grown, especially locally-grown cut flowers, require far fewer resources to get crops from Point A (the farm) to Point B (designer), fewer, if any, chemicals to preserve flowers during transport, shorter transport times, less fossil fuel, less packaging, less single-use plastic. When sourcing locally, I also get to know farmers by name and understand how much they care about their farming practices and witness the depth of their knowledge on cultivating flowers in the extreme conditions the midwest offers.

Debra Prinzing, founder of the Slow Flowers Movement explains:

“The Slow Flowers Movement recognizes that there is a disconnect that has disengaged humans from small-scale flower farming. It aspires to take back the act of flower growing and recognize it as a relevant and respected branch of agriculture in the U.S.

“In a way, this also means that we redefine beauty. As a Slow Food chef cooks with what is seasonally available, a Slow Flowers florist designs with what is seasonally available.”

As part of the Slow Flowers Society, I am transparent with my clients about where flora are sourced. Sometimes this means certain flora we’ve grown accustomed to seeing for specific seasons and/or holidays just aren’t available. I hope that kind of transparency brings into focus a more complete picture of how sourcing from local specialty-cut flower farmers connects to safeguarding the health of our ecosystems and building economic justice.

To highlight an example closer to home, the freshly formed Flatland Floral Collective, a growing group of eastern Nebraska and western Iowa specialty-cut flower farmers, meets once a month to bring together their flora harvests in Omaha and make them available for purchase to florists, designers, and then the public. It’s similar to a farmer’s market specifically composed of all flower farmers. Many larger cities have flower markets similar to this model that gather weekly, even daily. It's a BIG deal for the burgeoning Slow Flowers movement happening in eastern Nebraska and western Iowa’s floral communities.

Traditional floral school didn’t teach me about the ecological harms inherent to floral industry trends popularized on social media. With time, experience, and research I learned how to spot these harms and nuances. I remember early in my floral design practice being drawn to a pure white palm leaf. I had never seen anything like it, and was intrigued. When I learned about the bleaching process used to erase the plant’s chlorophyll, the chemicals involved and the conditions workers were exposed to, I adopted an “ecosystems over aesthetics” approach to design. Sure, a pure white palm leaf was beautiful, but it pales in comparison to the beauty of a healthy ecosystem performing all its life-giving functions.

Slow Factory founder, Celine Semaan-Vernon says:

“Ecosystems over aesthetics is the intentional prioritization of environmental justice over the whim of the creative and aesthetics. New forms of aesthetics must be explored that enter the paradigm of becoming nutrients to their ecosystem rather than poison. This fundamental design constraint must be adapted by all industries, if we are to avoid climate collapse, mass extinction, and all other catastrophic results of centuries of extractive and polluting imperialist capitalism” (Semaan-Vernon 2021).

Sculptures by Blair Buswell at Pioneer Courage Park, Omaha, NE. Left image: Depicts a Native American engaged in dialogue with land colonizers. Right image: Land colonizer carrying a gun with dried sedum flora tied to it by District 2 Floral Studio. (February 2022).

The design constraint concept of valuing ecosystems over aesthetics guided me to make design choices rooted in reducing environmental harm while promoting social equity. Choosing a material based solely on its trend-worthy aesthetic and ignoring the harm to workers and environment ecosystems was no longer a viable option for me. I chose not to engage.

Here are a few trends we can avoid as designers, consumers, and an industry to collectively move the needle toward integrating ecologically sensitive design practices as the norm rather than the exception.

Artificially Bleached Botanicals

Artificially bleached baby’s breath (gypsophila) and sedum. Photo taken at a local craft store (2022).

Artificially bleached botanicals are usually an entirely pure white botanical (stems, leaves, and petals) that have undergone chemical-bleaching to pull the chlorophyll from their being. Sustainable flower farmer, Linda D'Arco, found the artificial bleaching process involves toxic chemicals including hypochlorites, sodium chlorite, peroxide, hydro-sulphites, borohydride, sulfur dioxide, and glycerin. To preserve the stark white color, botanicals are coated in "water soluble plastic" after bleaching.

Not only are those processes extremely hard on the plant’s body, but the run-off is toxic to the environment and impacts even the smallest of organisms in our waterway systems. The residue from the bleached botanical is also passed onto the skin of anyone who handles them. Despite these harms, they’re readily available to consumers without disclaimer in any craft store. I experiment with the sun to naturally lighten a flower's color instead, an alternative that doesn’t pose the same harms to our ecosystems or our health.

Painted and Dyed Botanicals

Dyed/Painted pussy willow tips. Photo taken at local wholesaler (2022).

Painting and dyeing botanicals is another trendy — though harmful — design practice. Most paints are plastic-based and eventually find their way into our waterways. In fact, paint runoff accounts for more than half (58%) of all microplastics in our streams, rivers, and oceans (Hailstone 2022). While fuschia prairie grass, hot pink anemone, blue carnations or tie-dyed roses might be aesthetically striking, that doesn’t mitigate the harms intrinsic to their production on micro-organisms in waterways, workers dyeing, dipping, spray painting and packaging, or designers working with them.

Boutonnieres created by District 2 Floral Studio using a spectrum of colors naturally found in flowers (May 2022).

Flowers gift us a brilliant palette of colors on their own. In their natural, ephemeral state, they are compostable and return nutrients to the soil when they decompose. Why coat them in artificial plastic color that creates waste when there was none to begin with? Creating with flora in their unaltered state instead offers the creative constraint of “ecosystems over aesthetics,” that leads to transparent conversations with others around the easy to overlook harms of painting pampas grass fuchsia. It has also led to new and strengthened relationships with local, seasonal flora, and growers.

Floral Foam

In the 1950s, the plastics industry created a large marketing campaign celebrating single-use plastic (Schiros 2022). Floral design prior to 1954 was made without foam. But because it has become a staple of floral design programs globally, it is also a mainstay in florists’ toolboxes (Feasby 2022). Today, despite repeated scientific findings about the harms consumption and waste perpetrate on our ecosystems, reliance on single-use plastics still dominates our lived experience. So why is floral foam still taught in design schools as a structural building mechanic?

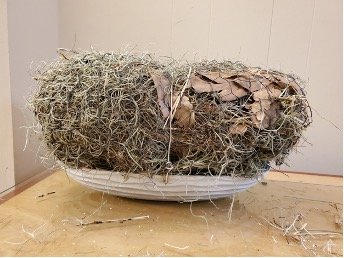

Reusable chicken wire wrapped around dried grass and leaves wired to a tray, used as an impact-conscious option by District 2 Floral Studio in place of foam (2022).

When I need a sturdy structural building mechanic as a base for a design, I opt instead to create grass burritos – rolling dried grass and leaves into chicken wire. This is a reusable design structure and is compostable if disassembled, and chicken wire can be reused. There is so much space for creative exploration into foam-free building that values ecosystems over aesthetic as a foundation – moss, fungi, gnarled vines, and branches are others with which I've experimented. Becky Feasby, of Prairie Girl Flowers, compiled a list of truths about floral foam.

Floral foam truths:

It is a single-use plastic (both Oasis green “wet” bricks, or the gray/green “dry” bricks are in this category).

It is a PF foam that is produced from petroleum-based phenol, with the addition of formaldehyde.

It breaks down into microplastics that contaminate aquatic ecosystems.

It should NEVER be disposed of down the drain (or, for example, soaked in a bathtub).

Floral foam with ‘enhanced biodegradability’ is still plastic.

More complicated truths:

Even after knowing better, some florists continue to use foam.

Rarely do consumers ask for floral foam in their arrangements.

Venues sometimes prescribe ‘water-free’ arrangements, which creates a predicament for florists who need to deliver what their clients want, but also meet the needs of the venue.

Manufacturers continue to engage in greenwashing campaigns aimed at encouraging florists and wholesalers to use their products, despite the known environmental hazards associated with floral foam. (Feasby 2022)

Bricks of green “Oasis” foam and gray foam taped to a tray as a structural design element. Photo taken after the flora was disassembled during a traditional floral design school course (2021).

“The industry of waste is causing immense damage to ecosystems around the world. Waste does not exist in nature, it is a human construct introduced by colonialism” (Semann-Vernon, 2021). When we focus the human construct of waste through a lens of intersectional environmentalism the concept of “waste colonialism” as "the transferring and moving of waste from a country exerting its power to lands and territories to countries (not their own) with less power” becomes more legible too.

“By practicing waste colonialism, the Global North unjustifiably exerts dominance over other countries by threatening their lands, waters and ecosystems, where the receiving nations lack the systems to safely treat such waste that they themselves did not even create" (Schiros 2022). Waste also disproportionately affects intentionally exploited communities, often Black, Indigenous and people of color, whose neighborhoods have historically, through discriminatory redlining pratices, been relegated to close proximal relationships with landfills or waste treatment facilities.

Growing in Grace

With all of that said, and given the urgency of adopting ecologically-sensitive design practices across every sector of our economy in the face of wide-spread environmental collapse, there is value in allowing ourselves grace in our individual and collective journeys toward impact-conscious design practices rooted in intersectional environmentalism.

I share these tangible shifts I’ve made within my own practice to center my reciprocal relationship with Nature, my dependency on her, and my connectedness to her. I share all of this in the hope that others examine their consumptive habits more thoughtfully and consider the unseen ecological impacts of one’s creative habits. My hope is that more designers choose to place ecosystems over aesthetics, and that companies become more transparent in disclosing the ethics of their production practices. Consumers can help guide the process by choosing not to purchase flora that have been toxically altered. Bridging the gap between beautiful designs and ethical production can be a priority (Daniari 2021).

For me, it is a gift to work with what nature offers. Growing community around designing more responsibly is a big dream but it is also an integral part of my practice. We are of the natural world, not just in it. We are ephemeral, just like nature. I still have more to learn on my journey toward developing an ecologically sensitive design practice, but I’m thankful for my fellow travelers who walk with me and light the way.

Branch Cloud installation in a home, created with nature elements sourced locally by District 2 Floral Studio (June 2022).

Ways To Grow An Ecologically-Sensitive Design Practice:

Explore growing your own plants & flowers, observing how they shift with the seasons.

Source flowers directly from local flower farmers (farmers markets), and/or look for the US-grown seal on market-sourced flora.

Purchase flowers from florists who actively source seasonally from local and/or US growers.

Follow Flatland Floral Collective to know more about eastern Nebraska and western Iowa locally-grown flower pop-up events that will be happening this season.

Reach out with any questions via email (district2floral@gmail.com) or on Instagram @distriction2floral - I love talking about practicing mindful reciprocity!

Experience the energy of this practice for yourself. Customize your own eco-friendly bouquet or integrate floral into your next event, photo session or project.

Consider micro adjustments or alternatives you might explore within your own creative practice that place ecosystems over aesthetics.

Notice the ephemerality and ever-shifting changes around you.

Holly Lukasiewicz explores flora design through an impact-conscious lens of sustainability as District 2 Floral Studio, valuing land ecosystem health, over trending aesthetics. Holly’s background is in K-12 arts education, and she continues to guide creative-making experiences with community groups as a teaching artist with nonprofits, seeing these connections as a way for participants to grow compassion toward self and others. Holly supports the role of creative practices as an approach to activism, weaving awareness and action around environmental, social and economic concerns.

Key Concepts:

Compostable: is when a product is capable of breaking down into natural elements in a compost environment. Because it’s broken down into its natural elements it causes no harm to the environment. The breakdown process usually takes about 90 days. (Toketemu 2022)

Ecosystems over aesthetics: a fundamental design constraint that intentionally prioritizes environmental justice over the whim of the creative and aesthetics. New forms of aesthetics must be explored that enter the paradigm of becoming nutrients to their ecosystem rather than poison. Developed by Slow Factory founder, Celine Semaan-Vernon. (Semaan-Vernon 2022)

Flatland Floral Collective: a growing group of eastern Nebraska and western Iowa specialty-cut flower farmers. Once a month they gather their flora harvests in Omaha, and make them available for purchase to florists, designers, and then the public.

Flora: plant life

Impact-conscious: making conscious design choices with research into potential impacts they may have on environmental ecosystems through a lens of intersectional environmentalism.

Intersectional environmentalism: an inclusive approach to environmentalism that recognizes social and environmental advocacy justice as being intertwined – and that environmental advocacy that disregards this connection is harmful and incomplete. It focuses on achieving climate justice, amplifying historically excluded voices, and approaching environmental education policy and activism with equity, inclusion, and restorative justice in mind. It was developed by Leah Thomas. (Baker, Martinez 2022)

LANDBACK: a movement that has existed for generations with a long legacy of organizing and sacrifice to get Indigenous Lands back into Indigenous hands. It allows for envisioning a world where Black, Indigenous and people of color co-exist in liberation. (LANDBACK 2022)

Microplastics: extremely tiny pieces of plastic debris in environment ecosystems caused by the disposal and breakdown of consumer products and industrial waste from humans.

Redlining: a segregation strategy American cities began using in the 1930s that were based in prohibitive, racist and discriminatory home lending practices. In cities across the country, red lines were literally drawn on city maps by the federally-funded Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, identifying predominantly African-American and immigrant communities as “hazardous” and unfit for investment. (UNION 2022)

Reparations: compensation provided to those who have suffered wrongdoing or to their descendants. The term is especially used to refer to payments made (or proposed to be made) in the aftermath of war, slavery, or other forms of wide-scale systemic injustice. In the United States, reparations have been made to certain groups and proposed for others. Discussion of the topic often involves proposals to make reparations to people who have been the victims of brutal treatment and racist policies throughout U.S. history, including Native Americans and the Black Americans who are the descendants of the African people enslaved in the U.S.

Slow Flowers Movement: recognizes that there is a disconnect that has disengaged humans from small-scale flower farming. It aspires to take back the act of flower growing and recognize it as a relevant and respected branch of agriculture in the U.S. It places a priority on sourcing American-grown flowers, especially those sourced within/from surrounding communities. It was developed by Debra Prinzing in 2014, based on her book by the same name. (Prinzing 2022)

Specialty-cut flower farm: a farm who specializes in the cultivation of perennial and annual flowers as crops that are distributed wholesale to florists and designers, and then to the community.

Sustainable: daily practices that support a beneficial pattern of co-existing living conditions for all beings on our earth.

Waste colonialism: the transferring and moving of waste from a country, exerting its power to lands and territories to countries (not their own) with less power. By practicing waste colonialism, the Global North unjustifiably exerts dominance over other countries by threatening their lands, waters and ecosystems, where the receiving nations lack the systems to safely treat such waste that they themselves did not even create. It was first recorded in 1989 at the United Nations Environmental Programme Basel Convention. (Schiros 2022)

Sources:

Aguilar, Emi [@indigenizingartsed]. Indigenous Wisdom for a Creative Practice. Instagram, July 23, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/indigenizingartsed/.

Baker, Kamrin, Amanda R. Martinez. “A Conversation With Leah Thomas.” Good Newspaper: The Intersectional Environmentalist Edition, Issue 33, March 2022, p. 16-17.

D'Arco, Linda [@littlefarmhouseflowers]. Chemicals Used to Bleached Flowers. Instagram, July 23, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/littlefarmhouseflowers/.

Daniari, Serena. “Celine Semaan-Vernon is Using Fashion To Spark Social and Environmental Change.” The Huffington Post - Culture Shifters, 2021, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/celine-semaan-vernon-fashion-social-environmental-change_n_6063513fc5b6d34efbc5e869. July 23, 2022.

Feasby, Becky [@PrairieGirlFlowers]. “Is Floral Foam Still an Issue?” Instagram, May 8, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CdTP2_Mrj-r/.

Feasby, Becky [@PrairieGirlFlowers]. “The Invisibility of Issues In The Floral Industry.” Instagram, April 24, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CcvQiLLrLsr/.

“Rose Exports and Farms in Ecuador.” Flower Companies Blog, https://www.flowercompanies.com/blog/rose-exports-farms-ecuador. July 23, 2022.

Freestone, Camille. “Fashion Sustainability Is No Longer An Option – It's A Necessity.” Coveteur, Jan. 8, 2021, https://coveteur.com/2021/01/18/celine-semaan-interview/. July 23, 2022.

Hailstone, Jamie. “Paint is the Largest Source of Plastic in the Ocean, Study Finds.” Forbes: Sustainability, Feb. 9, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiehailstone/2022/02/09/paint-is-the-largest-source-of-microplastics-in-the-ocean-study-finds/?sh=a79c84d1dd80. July 23, 2022.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions. 2015.

“Manifesto.” LANDBACK, https://landback.org/, July 24, 2022.

McGee, Amy [@BotanicalBrouhaha]. Dreaming Big In Alignment With Your Own Values. Instagram, July 23, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/botanicalbrouhaha/.

Prinzing, Debra. “A Slow Flowers Manifesto.” Slow Flowers Society, https://slowflowersjournal.com/a-slow-flowers-manifesto/, July 23, 2022.

Semaan-Vernon, Celine [@TheSlowFactory]. “Ecosystems over Aesthetics.” Instagram, Sept. 30, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CUceOqBLClJ/.

Schiros, Dr. Theanne [@TheSlowFactory]. “History of Plastic.” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CNcqSeXFHt6/, April 9, 2021.

Schiros, Dr. Theanne [@TheSlowFactory]. “Waste Colonialism.” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CNdSQefFOPY/, April 9, 2021.

Toketemu. “What’s the Difference: Biodegradable and Compostable?” Nature’s Path, https://www.naturespath.com/en-us/blog/whats-difference-biodegradable-compostable/, July 24, 2022.

“Undesign the Redline.” UNION for Contemporary Art, https://www.u-ca.org/redline, July 24, 2022.